This is such a year of change for us all. And I think as a dramaturg I am inclined to try to think deeply and understand what on earth is going on both in the country and in the theater and what I can contribute to righting a ship that seems to be veering off course. The ship is veering, the ocean is roiling, and still we try to be of use. Like in “Fahrenheit 451,” we try to protect what we know, what we can preserve and what we can pass on to the future. And one thing we know from the history of theater is that all this has happened before – many times in fact.

When Oliver Cromwell took over England and Charles I was deposed in the Glorious Revolution, the first thing they did was close the theaters. The beheading of King Charles I only came three years later. The theater community fled to France for 40 years and returned after the Puritans’ defeat with a very changed art form – Restoration Drama – and women onstage in female roles in the place of male acting apprentices. And a newly French style in the plays that defined the new era. Utterly unlike the work of the era of Shakespeare and his contemporaries half a century before.

My year has been defined by remembering in print and on video the artists who created the American theater I was part of, so that the memory of their contributions will not be lost. So much of my work was devoted to rediscovering lost theatrical masterworks, and at the same time, understanding and supporting the innovative artists of the present who contributed to the great flowering of US theater during the years of my professional life. I was so lucky to be a part of it, and I want to try to document and preserve what I witnessed.

This year, I wrote two articles for American Theater – now, alas, very reduced in scale- to remember artists I knew and worked with who passed on early in the pandemic. This has become increasingly important as public information sources now draw from the public record, and without something in print as a source, a brilliant life and a body of work – especially directing and design work – can disappear.

I participated in a week-long celebration of director Robert Wilson, thankfully still among us, which discussed productions of many of his works that we – the symposium participants- had been part of. Organized by CUNY’s Segal Center, the entire week-long conference is available on Howlround. The video linked below shows a session with a few of us who were part of the creation of the premiere of “Hamletmachine” at NYU. And then we joined the larger group discussing Wilson’s many other works, with Wilson himself, and we all had the pleasure of spending the day at the end of the week-long symposium with him at his Watermill retreat.

Our “Hamletmachine” session is attached here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1jizv40s2k

Steve Carter

Remembering Playwright/Dramaturg Steve Carter

https://www.americantheatre.org/2020/09/16/steve-carter-playwright-and-playwrights-advocate/

Yale/Geffen produced Steve’s play “Eden” to great success this year and this article was circulated to the cast. Steve, a native of Nevis, a very old friend and colleague — always careful about details and always considerate – was in a nursing home in Texas where he had moved to be near his nephew- his only remaining relative. In the home, he was infected with Covid just as the pandemic began. He worked with me on the piece on email, gave me his final corrections and died the following day. The piece is quite an extensive record of the day-to-day work of the early days of the Negro Ensemble Company and his many contributions later as head of their writers’ unit.

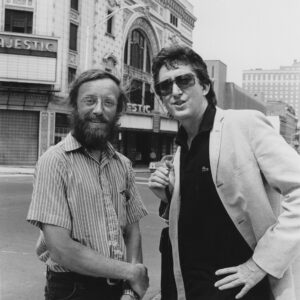

And once again American Theater was kind enough, shortly after his death, to publish my reflections on the enormous contributions of director Adrian Hall, with whom I worked many times. As a result, I received a call from the obit desk at the Times, asking for more details – such as place of death – which I did not have. But Adrian got his Times obit and with it a chance to be remembered on Wikipedia where he most definitely belongs. The piece below is dated, to put it mildly, in one regard, as the reader will see. It’s far longer than the Times obit – filled with amazing details about his life and work. I’ve added an informal picture of Adrian and Eugene Lee in their early years to begin.

EUGENE LEE AND ADRIAN HALL

Adrian Hall – An Appreciation

Adrian Hall, founder and former Artistic Director of Trinity Repertory Theater from 1964-89 and Artistic Director of the Dallas Theater Center from 1983-89, died on February 4th 2023 at the age of 95 at his family’s 150-year-old home in Van, in NE Texas, population today 2000, population 800 in his youth, after a long, lonely struggle with Alzheimer’s. Surrounded during his life by his long-term collaborators, his beloved mother and sister, his nieces, his life’s companion, composer Richard Cumming and his devoted assistant and former board member Marion Simon, Adrian who expected to die surrounded by family and friends, nursed each of these beloved family members until their deaths and lived the final decade of his life alone. In what I know to be the highly unusual and resonant way his life unfolded, his longest and closest collaborator – designer Eugene Lee -died exactly forty-eight hours later in New England.

Eugene Lee’s passing was widely noted, of course, because of “Saturday Night Live,” an Adrian Hall set if there ever was one, as well as his Tony Awards for “Candide,” “Wicked” and “Sweeney Todd.” The 70+ sets and the designs of two theaters for Hall went unmentioned. “It’s a miracle we met…He saved my life,” wrote Lee once in a tribute to Hall. “He took me in… He’s some kind of unusual genius…Pretty pictures don’t interest me. Adrian wasn’t interested either. Space interests me. Process interests me. In his book, “The Empty Space,” Peter Brook says he had a set designer build a model for his first Broadway play. At the first rehearsal, he threw it all away, Adrian was like that. Adrien always had principles behind what he did. He was wildly enthusiastic. In all those years, Adrian never had an office in the building. He never had a production meeting.” Lee added, “The world at large has absolutely no knowledge of Adrian’s work. In my case, people just know me from my Broadway and TV work. The REAL work, nobody knows anything about…”

Hall left Van in the late 40’s and, like so many others, had a life changing encounter with Margo Jones, the Texas Tornado and the mother of regional theater (“Leave New York!” was her motto) who discovered Tennessee Williams and co-directed the world premiere of “The Glass Menagerie,” as well as Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee‘s “Inherit the Wind.” As she did with Horton Foote, Jones sent Hall to the Pasadena Playhouse to apprentice after a year of college – his entire education. In 1959, Hall was drafted and sent to Germany where he saw Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble. Grotowski’s work was soon a major influence, as well as his new knowledge of Meyerhold. As he later said at Trinity, “it was important to me to let these people in Providence, Rhode Island, know that art – as Brecht said – ain’t nice, Darlin’. It’s got warts, it’s ugly and it’s infuriating as hell. But boy can it be outrageous. It’s the only craft that I know that has the potential to change men’s souls.”

Tall, handsome, interested in everything, Hall had a highly focused, unusual way about him – brilliant, uncensored, curious about the opinions of others and brutal at times. It was thrilling and, for many, scary to be around him. He was surrounded by acolytes throughout his career, and absolutely fearless when standing up for his beliefs. “Being gay, well, it’s an outsider status, no matter what anyone else says, and part of me really likes that. It keeps me on edge, keeps me aware of not being fully accepted, what it’s like being scorned and thought less of because you’re different. I identify with society’s rejects. Always have. That’s what my work is about.” His father could never accept him, and he recalled, “When I left home to go in the army over to Germany, I can remember, so clearly, on the platform, my father taking me in his arms and hugging me. He wasn’t usually that demonstrative. I’ll never forget the feel of his arms around me.”

Hall moved to New York in the late 50’s and began directing, and after some standard rough beginnings, where he was replaced when shows he directed moved, he began to think about working in regional theater. In 1964, he was appointed Artistic Director of Trinity Repertory Theater in the then-depressed working-class former mill town of Providence, RI at a theater without a home, and there he began his work with designer Eugene Lee. The NEA has just been created. Trinity Square was deserted. Twenty years later, Trinity Rep had 20,000 subscribers, the theater’s operating budget was $3.7M, and it employed 150 people. An audience of 173,000 supported an eleven-play season featuring a full-time company of 37 actors, many of whom had moved to Providence to make it their home. Trinity Rep was awarded the 1981 Tony Award for Best Regional Theater. Hall and Lee staged Duerrenmatt’s “The Visit” in a site-specific production at the Providence train station. And most importantly, Hall created the Project Discovery Program with support from the NEA and the enthusiastic backing of the governor of Rhode Island, whereby every high school student in the state attended three Trinity Rep shows in each year of high school. “The Project Discovery kids couldn’t get connected with some boring stuff behind the proscenium arch. The little bastards were more interested in slashing the seats and tearing the plumbing out of the bathrooms. So Eugene and I just had to get at ‘em – frighten the shit out of ‘em. Make ‘em laugh and participate in action that was so fast and furious that they had little chance but to hang on or else!”

A young Viola Davis was one of those kids. She recalls:

Not only was I a “benefactor” of Project Discovery, I was in the last play he directed at Trinity: “Red Noses.” I got my Equity Card because of Adrian. He was one of the first big shifters of my life. The first play I remember was “Arsenic and Old Lace.” I want to say I was 14. I remember Richard Kneeland (GREAT actor) was in it. The effect it had on me? At 14, I made a personal declaration that I wanted to be an actor. I believed in its magic; its healing powers and I wanted the ability to extract myself from this world and enter another. I was mesmerized….by the costumes, the lighting, the artists AND, this was a big one for me coming from dysfunction, I felt I belonged. Adrian always had the ability to do that…make the community a part of the play. The actors, at any given point could be a train, break the fourth wall, physically be in the audience at times. He used actors of any shape, age and ethnicity and used them according to talent. His imagination was endless and brave. Trinity became a gathering place in a community where there were no gathering places for the whole. Thank you for keeping the memory of Adrian alive. I was 14 in 1980 and I believe that was the year Trinity won the Tony. He was a giant.

As the years passed, Hall’s approach gained its focus. He began with plays of extraordinary provocation and reach: classics, adaptations, gay plays, plays about abortion, hidden parts of American history and current events from Charles Manson, to classics from Racine to Arthur Miller and new plays by Julie Bovasso and John Guare. He learned to temper the controversial with the expected: a holiday “Christmas Carol,” and his audience continued to grow.

He never really learned to drive: he drove, but took his life – and his passengers’ -in his unsteady hands. He never opened his mail and was in trouble more than once for not paying important bills. The Governor of Rhode Island helped him out when he was in danger of losing his home and then joined Trinity’s board. A millionaire donor from New York took her life in her hands and allowed Adrian to pick her up at the train station in his car in a snowstorm, and arriving at the theater, threw her sable coat in the gutter so he wouldn’t have to get his feet wet.

Hall and Lee were developing their radical aesthetic: everything was stripped down. The action took place among the audience. The acting company was cross-cast ethnically, there was full-frontal male nudity, an on-stage abortion. That final item, in an adaptation of the cult James Purdy novel “Eustice Chisholm and the Works” brought things to a boiling point, and Hall’s real legend began. He was fired by his board for this controversial selection, although it had grossed more than any other play in that season. To the amazement of artistic directors across the nation, he responded by firing his board. The staff and acting company mounted a campaign to reinstate him, going door to door, writing petitions, and the board relented.

By now, Hall and Lee’s aesthetic was complete, forged from American roots but informed by European avant-garde masters. “All those scenic embellishments interfered with the spectator’s visceral emotional response to the performance. Hall and Lee reached two conclusions: 1. If the spectator is put in the position of pretending that the fake thing is real by being offered a trembling flat in place of a real wall or a rubber knife in place of an actual weapon when the action of the text offers real pain or emotional danger, the spectator is let off the hook and can retreat into a safe corner because it has been established that this is only make-believe and 2. If the spectator is presented with a highly decorative literal presentation of reality, the images have been so completely defined by the director and his designers that there is nothing left for the spectators to do but sit back and watch the passing spectacle. S/he is therefore discouraged from participating emotionally in the event. Everything would be real.”

Hall’s Holy Grail – a project that he pursued from the late 60’s to the end of his life with Eugene Lee and composer Richard Cumming was the work of Robert Penn Warren – a friend from CT they called “Red.” Hall was a political animal at heart, and two works by Red Warren preoccupied him for the remaining decades of his life. Both have to do with the frailties of American democracy and this country’s poisoned racial history. The first, which was done at Trinity (and included in the student performances) was Warren’s epic poem “Brother to Dragons” whose subject is a little-known event: two of Thomas Jefferson’s nephews butchered a slave for breaking a porcelain pitcher. A fascinating discussion arose about adapting Warren’s poem, and then a ground-breaking dialogue about how to portray it on stage. How do you actually hack someone to death? In Hall and Lee’s production, each night the actor brought on stage a large joint of meat purchased nearby and surrounded by the audience, actually hacked the bone apart with an axe. This was not an easy task, and the bone and flesh often flew into the surrounding audience. The results were electrifying, visceral and real -though the means were symbolic. The ultimate Hall/Lee realization.

Adrian, Lee and Cumming also tried for decades to adapt Warren’s great novel “All the King’s Men” for the stage. They worked on almost a half a dozen productions as they tried to find the heart and through-line of Warren’s fictionalization of the story of Huey Long- now so unbelievably prescient as we leave the Trump era behind. Huey Long (and Warren’s Willy Stark) were assassinated before the damage moved to the national arena, but the book looks closely at America’s flirtation with totalitarianism. Or rather looked – decades before the future we live in today. Adrian enlisted songwriter Randy Newman, and his music became the score of the productions. ‘Sail Away,” after all, is a song about a slave ship coming into Charleston Bay. At one point early on, I got involved in the development of the piece (I had worked with Adrian and Eugene on several Shakespeare plays at the Delacorte for Joe Papp during the 80’s) and we all broke our heads trying to decipher the through-line of a potential play adaptation that could come in to NY. The problem centered not on Willie Stark and his redneck supporters, but on the sympathetic high-born brother and sister who enable Stark’s rise – (just as it does today, as we’ve learned) and their fascination with him can be traced in the novel to an ancestral crime in their family in the time of slavery. Adrian directed this adaptation in different forms many times, in many venues, but it remained his unfulfilled holy grail.

As he approached 60, he was offered the position of Artistic Director at the Dallas Theater Center, then in a brand-new building by Frank Lloyd Wright (soon to be called Frank Lloyd Wrong) and feeling an urge to return to Texas, he endeavored for several seasons to run both huge theater complexes at the same time, flying between cities. For a while he did this successfully, winning a second Tony Award for outstanding regional work in Dallas. But the Dallas board, theater space and affluent Highland Park audiences were not to Adrian’s liking: the seating closest to the stage was reserved for donors and was often empty, Eugene didn’t feel that Wright understood the theater and they successfully pressured the board to allow him to redesign parts of the space. With that completed, Adrian gave notice at Trinity and decided to return full time to Dallas to be nearer to his family. He gave an interview to Kevin Kelly at the Boston Globe with some off-the-record remarks about his hesitations about the Dallas audiences and board, which Kelly printed. On the day the moving van with all his possessions arrived in Texas, he was informed by the Dallas board that his job offer had been withdrawn.

Adrian moved home to Van and his mother and sister and directed as a free-lance director around the country for a year, when the Artistic Director who had replaced him in Dallas the year before died unexpectedly, and so Adrian took the position for another few years. His replacement in Providence, upon arriving at Trinity, immediately fired the entire acting company who had purchased homes and whose children were in school there. Times were changing. Shortly after that, new artistic directors were appointed who would stabilize the theater. But the dream of a resident acting company repertory theater was gone, as it was in many other theaters across the US.

Oskar Eustis, now at the Public Theater, became one of the later artistic directors at Trinity. He was a fervent Adrian admirer and I include here his amusing excerpt from a souvenir book published by the theater at a tribute to Adrian.

“I first met Adrian in 1990 at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles. He was appearing on a panel with Kenneth Branagh and Leon Katz, the renowned scholar and writer who headed Yale’s dramaturgy program for many years. The panel was discussing contemporary approaches to the classics, and Adrian completely dominated the proceedings, weaving a spell-binding tale of how the entire professional theater in America sprang from the touring productions of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” how our field was created in the crucible of the anti-slavery struggle, how idealism and commerce had been mixed together from the very inception of our craft in the New World. It was a brilliant, voracious, funny performance. I was absolutely captivated.

Afterwards Leon, brilliant, septuagenarian, cynical, said, “I would follow that man into hell.”

He inhaled his ever-present cigarette, paused, and added, “Of course if he was teaching theater history, we’d have to fire him.”

But Adrian never claimed to be a historian. He was, and is, an artist, a shaman, a storyteller, who willed Trinity into existence and led it to prominence and glory for over a quarter of a century. He was one of a handful of pioneers who founded the American Regional Theater: Zelda Fichandler, William Ball, Garland Wright, Tyrone Guthrie and other glorious visionaries who planted theaters across the country and created the profession that so many have since devoted their lives to.

During 2024-5, thanks to Tony Kusher who suggested this, the Library of America decided to publish the collected words of John Guare – my great friend and colleague.

John Guare: Plays (LOA #392)

by John Guare

9781598538168

PenguinRandomHouse.com: Books

Tony had organized a celebration at the 92nd St. Y for John’s 80’s birthday in February, 2024- a year ago – and the LOA book began then, edited by Michael Paller, now a new great friend, with an introduction by John Lahr. I was engaged to suggest to the LOA staff (who work primarily with poets and prose writers) which plays to include – and this turned out to be an incredibly difficult, year-long task. I emerged from it with major insights about where we are in the profession today – see my thoughts at the end.

Here’s the initial list of John’s plays, musicals and films:

Over the spring and summer, I reread and pruned this enormous oeuvre and sent a far smaller selection to LOA and to John. This was an extremely difficult task since I was dealing with different, revised, re-published versions of many of the plays, as well as screenplays, musicals lyrics etc. John rethought, rewrote, republished and had new productions of new versions of many of his plays. LOA had no idea that John’s oeuvre was so large.

Our target ‘symbol’ count (in their bold numbering below) was 774 and here was my first cut – printed with LOA’s annotations:

1966: Something I’ll Tell You Tuesday [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 13

1966: The Loveliest Afternoon of the Year [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 9

1967: A Day for Surprises [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 8

1968: Muzeeka [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 25

1971: The House of Blue Leaves [Viking: 1972] 67

1974: Rich and Famous [Rev, unpublished text, 2002] 58

1977: Landscape of the Body [Grove Press: 2007] 64

1979: Bosoms and Neglect [DPS, Rev:1999] 63

1981: In Firework Lie Secret Codes [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 13

1982: Lydie Breeze Trilogy [DPS, Second Rev: 2022]

Part One: Cold Harbor 89

Part Two: Aipotu 59

Part Three: Madaket Road 59

1990: Six Degrees of Separation [Vintage: 1990] 67

1992: Four Baboons Adoring the Sun [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 55

1993: New York Actor [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993]10

2002: Woman at a Threshold, Beckoning [rev, unpublished version] 18

2002: A Few Stout Individuals [Grove Press: 2003] 83

2010: A Free Man of Color [Grove Press: 2011] 74

2011 Elzbieta Erased [The Best American Short Plays 2011–2012, Hal Leonard: 2013] 21

2019: Nantucket Sleigh Ride [DPS: 2022] 59

Backmatter [Chron, Notes, Note on the Texts] 70**

**Pages for backmatter is an estimate.

——————————————————————————

Current estimated total: 984

The maximum number of pages for this volume is 848, inclusive of backmatter. Approximately 136 pages need to be cut from the list above. A few of the trade editions include a foreword, preface, or production notes—the nomenclature varies—by JG, and these page counts reflect that frontmatter: The House of Blue Leaves, Landscape of the Body, Six Degrees of Separation, and A Few Stout Individuals. If that material is not to be included in the LOA volume, then subtract twelve (12) from the count for Landscape of the Body, two (2) from Six Degrees of Separation, and four (4) each from The House of Blue Leaves and A Few Stout Individuals.

Collations of texts will need to be undertaken for all editions, with a handful of exceptions (those revised plays previously earmarked by Anne).

My email with this info and my edited list of his works here above reached John in the morning, and by evening he edited the reduced list and returned his final selection – a perfect score: 778.

Date: Monday, 15 July 2024 at 23:43

Subject: Fwd: LOA 778 magic number

These are my choices for the LOA/TOC. I can’t believe it but they appear to add up to exactly 778.

xxxx

1966: Something I’ll Tell You Tuesday [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 13

1966: The Loveliest Afternoon of the Year [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 9

1967: A Day for Surprises [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 8

1971: The House of Blue Leaves [Viking: 1972] 63

1974: Rich and Famous [Rev, unpublished text, 2002] 58

1977: Landscape of the Body [Grove Press: 2007] 52

1979: Bosoms and Neglect [DPS, Rev:1999] 63

1980: Atlantic City Screenplay [Text from John Guare] 56

1981: In Firework Lie Secret Codes [Four Baboons Adoring the Sun & Other Plays, Vintage: 1993] 13

1982: Lydie Breeze Trilogy [DPS, Second Rev: 2022]

Part One: Cold Harbor 89

Part Two: Aipotu 59

Part Three: Madaket Road 59

1990: Six Degrees of Separation [Vintage: 1990] 65

2002: Woman at a Threshold, Beckoning [rev, unpublished version] 18

2002: A Few Stout Individuals [Grove Press: 2003] 79

2010: A Free Man of Color [Grove Press: 2011] 74

The pub date for the LOA volume is Sept. 25, 2025.

As the year progressed and I reread John’s plays in their many versions, many in acting editions, I realized the enormous group of actors who either worked with John very early in their careers or found their first successes in his plays: Linda Lavin, Sigourney Weaver, John Mahoney, Elizabeth Marvel, James Woods, Cynthia Nixon, Raul Julia, Ben Stiller. I’ve come to think that a body of work of this scale, which ranges so widely in content and form and so perfectly understands the stage and all that it is capable of, may be an endangered species at the moment. I have always seen it in Beckett, in Shepard, Tina Howe, August Wilson, Caryl Churchill, Adrienne Kennedy and Lanford Wilson (who once told the LCT Directors Lab that because he had surrounded himself with the actors of Circle Rep for so long, as a result his work which began with the experimentation of The Gingham Dog, Rimers of Eldritch, The Mound Builders, and Burn This had become more tied to convention as his friendships and understanding of the actors’ processes moved him to write for his and Mashall Mason’s company.) A similar brilliance and range is evident earlier in the plays of Jean Genet and Thornton Wilder – both geniuses. When John Guare writes the stage direction, “She goes into the dark” in Landscape of the Body it’s like a body blow- a perfect understanding of the stage. A great play to reread.

This spring marked the first anniversary of the death of English playwright Edward Bond – given a Times obit but largely uncelebrated and unremembered here. To slightly compensate and just do something (!), the Segal Center (again!) devoted an evening to his memory on the first anniversary of his death.

Here’s his Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Bond

Just look at the four films he wrote and who directed them! And how his first play Saved made the reputations of so many of his era’s most renowned directors. And later, his play Bingo about the final years of Shakespeare’s life in Stratford – about which we know surprisingly more than his entire time in London portrays him (as does the small public record of the time) devoted to seeking a title, a coat of arms, a large house, and an impressive burial site – all at the time the rural enclosure actions were beginning in English history in towns like Stratford-upon-Avon. It’s a brutal and controversial play. Bond was a tough one and took everything and everyone on. David Hare and Caryl Churchill are his heirs.

The oeuvres of even our best young writers now are so meagre in comparison to the scale of these writers’ work – let’s add in O’Neill, Ayckbourn, the great Brian Friel. Once playwrights today – mid-career – go into a TV writers’ room, it’s over. Their work is dead.

Zoom Classroom Visits 2024-5

I’ve enjoyed visiting classrooms from Providence to Honolulu to speak over Zoom to students of dramaturgy during this past year and respond to their questions and to their work.

To some degree, it’s also been confusing, and I’ve come to realize how much our profession has moved from actual theater conservatory training (Stratford, Louisville, ACT, Pasadena Playhouse, Goodman etc) into colleges and how little contact students now have with life in the profession. Nobody’s learning by carrying spears and watching the interactions between the leads and the director, or sewing in a costume shop and listening to the info the dressers overhear in the dressing rooms and bring back there. Of course, so many theatres have closed now, and colleges departments always had jobs to offer to people of my generation who became less active in the field. Add to this the incredible rise of the influence of critical theory – unknown in the profession itself – which had barely begun when I left grad school, and what now appears to be its demise – to my surprise there are already books in print on “The Death of Theory.”

Sometimes in these classes, I’ve found myself feeling more like a football player – trying to point out that what works in the theatre is the result – when successful – of a team where each participant excels in their position, has played the game since childhood, knows its history in many particulars and understands and relishes its group dynamic. That’s what you have to work with- a team. A dramaturg’s niche may include history, and literature, and languages and information about the past and the countless ideas that inform the play now as well as back at the time of its creation in its first incarnation before a public. And you need to know who each public was. But if the group can’t or won’t take the ideas up, the information is of no use. I remain continually astonished in each professional situation I’ve been a part of at what each company finds interesting and what ends up informing the production. Much of my book is devoted to describing this. In the appendixes, I include lists of my own “100 Interesting Facts” about several shows I worked on, and in each case only one or two of these facts or ideas ended up informing the final production. Just like an actor who tries an equal number of things in beat after beat in the rehearsal room, I consider the inclusion of any of my contributions a success.

I’ve been surprised that many students appear now to bring with them tremendous judgement and fear of certain kinds of knowledge – knowledge that, I gather, must be unwelcome in their academic environments. This is hard to reconcile with the outsider freedom of the theatre world. And I’m speaking of all theatre from the past, (my god, look at The Bacchae!) as well as from my own experience in recent contemporary times. In a Zoom class recently, upon hearing the subject of a student project about explosive contemporary political events (always a good subject for plays) I mentioned the fact that it was interesting that George Floyd and Derek Chauvin had known each other. They worked security in the evenings at a local club – one inside and one outside. Not friends by any means, I gathered, but they knew who the other was. I offered this in the spirit of “here’s a piece of information/fact that somebody might find interesting” as I have so many times with plays from Aeschylus to Adrienne Kennedy, and I felt a sense of absolute horror arise from the zoom room. I had inadvertently stumbled into something that could not be spoken.

What struck me as dangerous is that this response is the exact opposite of what a theatre collaboration needs: the freedom for actors, and designers, and directors to say, “What if I try….” and afterwards the wise response may well be, “Ok, interesting. Let’s hold this for now.” And a good actor or designer will be ready immediately with idea #2. Or #10. And the larger group will be learning something. But without the freedom to experiment, and show things, (some dangerous) the exploration will be so narrow. I mean look at all the taboo things going on – both personally and politically – in Hamlet.

I think it would be fascinating to take a highly regarded production of a complicated play and compile a list of the hundreds of suggestions by members of creative team that were tried in that play’s rehearsals -but never used. And then – without identifying which ideas came from whom- list the names of the artists in the company. Out of the mess of life, in strange collective ways, comes insight.

I remember doing a platform event at Lincoln Center Theater with the cast of Horton Foote’s play, “Dividing the Estate” shortly before the run ended. And what a radical writer he was in his own quiet way! Actor Penny Fuller, who played the daughter-in-law of the central, highly dysfunctional family, told us that all actors like to have a secret that they never tell anyone else involved in the production, but which informs their performance. She wanted to tell us hers, now that the run was at its end. Despite the absolutely horrific dynamic of this family, her character of the daughter-in-law was always cheerful as she wandering in and out of the rooms where the family fought. “My secret is I just found out that I am pregnant.”

LMDA DRAMATURGY BIBLIOGRAPHY AND IN-PROGRESS WIKIPEDIA DRAMATURGY PRODUCTION CREDITS

To end with the big reveal, at the COVID lockdown, with all our theaters closed and nothing constructive to do, a large group of dramaturgs began an initiative to record the work of our profession in the United States so that it would appear correctly on Wikipedia and, I assume now all the other information sources that were just ideas even back then – a mere 5 years ago. I wrote a short introduction to the entry outlining the work of early US dramaturgs from the beginning of the 19th Century up to the founding of the regional theatre movement in the early 1970’s when so many theaters across the country were built with Ford Foundation money. Then we reached out to the field on email and created a Google Docs form organized by contract type and amassed a large data set spanning two time periods: 1975-2000 and 2000-2020 – covid lockdown. Many, many dramaturgs added their credits from operas, Broadway shows, LORT A, B, C and D houses, as well as Off-and Off-Off Broadway productions. Many contributors are still missing. And some have already passed away.

Geoff Proehl has been keeping an extensive bibliography of published work in and on the field, and he was also instrumental in moving this new Wikipedia project forward with the help of LMDA – and with Wikipedia Education, who were eager to add us in, as they are always looking to include more women and so many of us were represented.

This project stalled and I am putting what exists so far here under a new Post-it on my old stage door mailbox on the site’s opening page, the two docs are labelled LMDA Bibliography and Dramaturgy Production Credits on the Web. The latter is still very incomplete. The initiative stalled for two reasons. Since the pandemic, life has changed so radically that much information online is no longer reliable or factual and as a result, everything posted now must be sourced. This will not be a surprise to anyone. But for us, since the internet was not used widely until the turn of this century, the record of so many of our contributions only exists in or on older established archives – IBDB, the Lortel Archives, in published books on dramaturgy such as Geoff’s own “Dramaturgy in American Theater,” which he published with his co-editors for Random House in the 1990’s. Theater websites did not exist then and today we find that the archive sections on sites at many regional and small theaters have pruned or even erased collaborators from their earlier seasons in their on-line histories. The show posters and the playwright and director are often all that remain.

Thanks to LMDA’s current president Sara Freeman, who assigned a student to begin the linking process in the work database, and despite making some excellent progress with this enormous task, we still are unable to upload to the internet the information about our profession and our contributions. Those of us who began this don’t have the technical abilities to complete the project and despite missing a chance or two to recruit help at theatre conferences, we’ve gotten nowhere.

Wikipedia even offers classes in how to do this work, but they require a teacher to devote an entire semester to the task of finishing a few entries, and most teachers want to do other things as well.

Even in these five years since the lockdown as the data was being compiled and sourced in our Google Doc for Wikipedia, and its archive, Wikipedia itself is already be being overtaken by AI and other knowledge forums.

Two closing thoughts that oddly book-ended this initiative: my brother, a tech bro, follows an influencer named Tom Nichols, a Jeopardy champ in recent years and now a political commentator with followers in the millions. A young woman Jeopardy contestant identified herself as a dramaturg (I tracked her down as a student at UCDC) and Nichols posted, “I have no idea what this is.” My brother helpfully posted an Amazon link to my newly released book to Nichols’ 3M (!) followers. Didn’t move the needle on sales as far as I could tell. But recently, five years later, I was searching for a date of an article I published and went on Google – I don’t know that I have ever googled myself which tells you more than enough about my age – and scrolling down several pages (I wrote for many magazines, did a lot of press and worked for 30 years at LORT A houses so there’s a lot online- and searching down about 15 pages of entries I recognized from my past, I found a tiny, single untitled line of text that when I clicked on it, opened to be (without a source) my entire book. I can only assume AI. I sent the link to my editor at Yale Press. She sent it to legal and they took it down. That’s how far we’ve come.

We – not others – should be in charge of documenting our achievements.

And so, a draft of where we are as credited dramaturgs, along with the enormous bibliography of writing about US dramaturgy in books, journals, and academic papers that Geoff completed to document our field here in the US from its beginnings in the 1970’s up to last year also sits here on my site in a read-only version behind a colourful stage door mailbox Post-it. The production documentation – also read only- though 30+ pages long- is wildly incomplete. We need to finish it. And that ‘we’ includes anyone reading this post.

The Wikipedia project needs collaborators who understand how to take it to the next step. Some things ARE on the Wikipedia archive already – an important step, but in general, filling out and finishing this vital project is simply above our paygrade. It really belongs to another generation comfortable with what is required to complete it. I’ve communicated with a few people not in the theatre who tell me, “Oh, that shouldn’t be hard,” but no group in our field has stepped up to help do this – besides Sara.

To me, old and now retired, it seems like the task of writing a history of, say, the Franco-Prussian War. How difficult can this be?

We remain invisible since we have done the work, but not documented it after the fact- a large failure in the modern age.

Any thoughts on this project are much appreciated – this website has an email. Besides looking for advice and help completing this, we’re also looking for documented (linked) production credits. Publication credits in book or journal form (not production credits) should be added through LMDA to the bibliography – which is enormous. It’s here on my site below, but in a read-only form. LMDA is managing it.

I’d also welcome thoughts about our profession in our changing times. With an attorney, we made a model contract some time ago for dramaturgs to use – it’s also on the LMDA website. I worry so much – as we all do – about the health of the theatre in general right now and how few works of real depth are even being written- and I do not mean ‘plays’ comprised of nostalgic music- jukebox musicals – or children’s books or movie adaptations, or vehicles for movie stars without stage experience. Somehow, Chekhov still seems to be surviving, and the Irish Rep has a bottomless reserve of greatness to draw from. And there are now many new writers dramatizing new stories from communities we have not often heard from. How will these scale up in the times we are living in and how do we encourage the creation of big, ambitious oeuvres like those cited earlier in this post that revolutionized the drama of the recent past? We were weaned on “Nicholas Nickleby,” and Edward Albee and his writers at the Aberwild Theater that he and his Virginia Woolf producers underwrote financially: Sam Shepard, Adrienne Kennedy, Samuel Beckett, Terrence McNally and others. Not to mention the artists of the huge downtown avant-garde arts scene…where is this world flourishing now?

Let’s try to preserve our own contributions and let’s move the art form forward. The read-only LMDA Dramaturgy Bibliography and the Dramaturgy Production History in the US are linked behind Post-Its on the old stage door mailbox on this site’s opening pates.

I found a piece on the web recently by an author of a younger generation that resonated with my experience to a degree I had not thought possible for many years.

https://reactormag.com/the-theater-kids-at-the-end-of-the-world/